Adieu au Professeur Piet Tommissen (1925-2011)

Quelques jours après avoir lu l’hommage publié par “Junge Freiheit” suite au décès du Professeur Helmut Quaritsch, l’ancien éditeur de la revue “Der Staat” (Berlin), j’apprenais, jeudi 1 septembre, en feuilletant sur le comptoir même du marchand de journaux mon “’t Pallieterke” hebdomadaire, dont je venais de prendre livraison, la mort du Professeur Piet Tommissen, qu’évoque avec une belle émotion le journal satirique anversois. Deux géants mondiaux des sciences politiques viennent donc de disparaître cet été, nous laissant encore plus orphelins depuis les disparitions successives de Panayotis Kondylis, de Julien Freund, de Gianfranco Miglio ou d’Armin Mohler.

A la recherche de Pareto et Schmitt

J’avais appris, tout au début de mon itinéraire personnel, où, forcément, les tâtonnements dominaient, qu’un certain Professeur Tommissen avait publié des ouvrages sur Vilfredo Pareto et Carl Schmitt. Nous savions confusément que ces auteurs étaient extrêmement importants pour tous ceux qui, comme nous, refusaient la pente de la décadence que l’Occident avait empruntée dès les années 60, immédiatement après les “technomanies” et les américanismes des années 50. Nous voulions une sociologie et, partant, une politologie offensives, contructrices de sociétés ayant réagi vigoureusement, “quiritairement” contre l’éventail d’injustices, de dysfonctionnements, d’enlisements, de déliquescences que le complexe bourgeoisisme/économicisme/libéralisme/parlementarisme avait induit depuis la moitié du 19ème siècle. Pareto démontrait (et Roberto Michels plus sûrement encore après lui...) quelles étaient les étapes de l’ascension et du déclin des élites politiques, destinées au bout de trois ou quatre générations à vasouiller ou à se “bonzifier” (Michels). Nous voulions être une nouvelle élite ascendante. Nous voulions bousculer les “bonzes”, leur indiquer la porte de sortie. Naïveté de jeunesse: ils sont toujours là; pire, ils ont coopté les laquais de leur laquais. Nous connaissions moins bien Schmitt à l’époque mais nous devinions que sa définition du “politique” impliquait d’aller à l’essentiel et permettait de trier le bon grain de l’ivraie dans le kaléidoscope des agitations politiques et politiciennes du 20ème siècle: que ce soit sous la république de Weimar, dans le marais politicard de la pauvre Belgique de l’entre-deux-guerres (le “gâchis des années 30” dira le Prof. Jean Vanwelkenhuyzen), dans les turpitudes des Troisième et Quatrième Républiques en France auxquelles De Gaulle, formé par René Capitant, disciple de Carl Schmitt, tentera de mettre un terme à partir de 1958.

Première rencontre avec Piet Tommissen dans la rue du Marais à Bruxelles

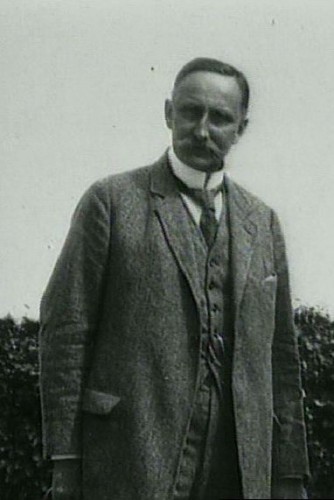

Il y avait donc sur la place de Bruxelles, un professeur d’université qui s’occupait assidûment de ces deux géants de la pensée politique européenne du 20ème siècle. Il fallait donc se procurer ses ouvrages et les lire. J’avais vu une photo du Professeur Tommissen dans un numéro d’ “Eléments” ou dans une autre publication du “Groupe de Recherches et d’Etudes sur la Civilisation Européenne”. Ce visage rond et serein m’avait frappé. J’avais retenu ces traits lisses et doux et voilà qu’en février ou en mars 1975, en sortant des bâtiments réservés aux romanistes et germanistes des Facultés Universitaires Saint-Louis, rue du Marais à Bruxelles, je vois tout à coup le Prof. Piet Tommissen, campé devant l’entrée du 113, à l’époque occupé par la “Sint-Aloysius Handelhogeschool”, où il dispensait ses cours. Il était impressionnant, non seulement par la taille mais aussi, faut-il le dire, par le joyeux embonpoint qu’il affichait, lui qui fut aussi un très fin gourmet et un bon amateur de ripailles estudiantines, ponctuées de force hanaps de blonde cervoise. Je suis allé vers lui et lui ai demandé, sans doute un peu emprunté: “Bent u Prof. Tommissen?”. Une certaine appréhension me tourmentait: allait-il envoyer sur les roses le freluquet que j’étais? Que nenni! Le visage rond et lisse de la photo, ancrée dans le recoin d’une de mes circonvolutions cérébrales, s’est aussitôt illuminé d’un sourire inoubliable, effet d’une sérénité intérieure, d’une modestie et d’une bonté naturelles (et sans pareilles...). Cette amabilité contrastait avec l’arrogance qu’affichaient jadis trop d’universitaires, souvent à fort mauvais escient. Le Prof. Tommissen était à l’évidence heureux qu’un quidam cherchait à se procurer ses ouvrages sur Pareto et Schmitt. Il m’a indiqué comment les obtenir et je les ai achetés.

Piet Tommissen et Marc. Eemans

Ensuite, plus aucune nouvelle de Tommissen pendant au moins trois longues années. Je le retrouve plus tard dans le sillage de son ami Marc. Eemans, avec qui il avait édité de 1973 à 1976 la revue “Espaces”. Je rencontre Eemans, comme j’ai déjà eu plusieurs fois l’occasion de le rappeler, à l’automne 1978, sans imaginer que le peintre surréaliste et évolien était lié d’une amitié étroite avec le spécialiste insigne de Pareto et Schmitt. L’histoire de cette belle amitié, ancienne, profonde, intense, n’a pas encore été explorée, n’a pas (encore) fait l’objet d’une étude systématique. De tous les numéros d’ “Espaces”, je n’en possède qu’un seul, depuis quelques semaines seulement, trouvé chez l’excellent bouquiniste ixellois “La Borgne Agasse”: ce numéro, c’est celui qui a été consacré par le binôme Tommissen/Eemans à l’avant-gardiste flamand Paul Van Ostaijen, dont on connait l’influence déterminante sur l’évolution future de Marc. Eemans, celui-là même qui deviendra, comme l’a souligné Tommissen lui-même, “un surréaliste pas comme les autres”. A signaler aussi dans les colonnes d’ “Espaces”: une étude de Tommissen sur la figure littéraire et politique que fut l’étonnant Pierre Hubermont (auquel un étudiant de l’UCL a consacré naguère plusieurs pages d’analyses, surtout sur son itinéraire de communiste dissident et sur son socialisme particulier dans un mémoire de licence centré sur l’histoire du “Nouveau Journal”; cf. Maximilien Piérard, “Le Nouveau Journal 1940-1944 - Conservation révolutionnaire et historisme politique – Grandeur et décadence d’une métapolitique quotidienne”; promoteur: Prof. Michel Dumoulin; Louvain-la-Neuve, 2002).

“De Tafelronde” et “Kultuurleven”

Tommissen, comme Schmitt d’ailleurs, n’était pas exclusivement cantonné dans les sciences politiques ou l’économie: il était un fin connaisseur des avant-gardes littéraires et artistiques, s’intéressait avec passion et acribie aux figures les plus originales qui ont animé les marges enivrantes de notre paysage intellectuel, des années 30 aux années 70. On devine aussi la présence de Tommissen en coulisses dans l’aventure de la fascinante petite revue d’Eemans et de Gaillard, “Fantasmagie”. “Espaces” fut une aventure francophone de notre professeur flamand, par ailleurs très soucieux de maintenir et d’embellir la langue de Vondel. Mais ses initiatives et ses activités dans les milieux d’avant-gardes ne se sont pas limitées au seul aréopage réduit (par les circonstances de notre après-guerre) qui entourait Marc. Eemans. En Flandre, Tommissen fut l’une des chevilles ouvrières d’une revue du même type qu’ “Espaces”: “De Tafelronde”, à laquelle il a donné des articles sur Ernst Jünger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Stefan George, Apollinaire, Edgard Tijtgat, Alfred Kubin, etc. Parallèlement à “Espaces” et à “De Tafelronde”, Piet Tommissen collaborait à “Kultuurleven”, qui a accueilli bon nombre de ses articles de sciences politiques, avec des contributions consacrées à Henri De Man, Carl Schmitt, Vilfredo Pareto et des notules pertinentes sur Thom et sa théorie des catastrophes, sur René Girard, Rawls et Baudrillard, sans oublier Heidegger, Theodor Lessing et Otto Weininger.

“Dietsland Europa”

Tommissen n’avait pas peur de “se mouiller” dans des entreprises plus audacieuses sur le plan politique comme “Dietsland-Europa”, la revue du “flamingant de choc”, un coeur d’or sous une carapace bourrue, je veux parler du regretté Bert Van Boghout qui, souvent, par ses aboiements cinglants, ramenait les ouailles égarées vers le centre du village. On sait le rôle joué par des personnalités comme Karel Dillen, futur fondateur du “Vlaams Blok”, et par le Dr. Roeland Raes, dans le devenir de cette publication qui a tenu le coup pendant plus de quarante années sans faiblir. Tommissen et moi, nous nous sommes ainsi retrouvés un jour, en l’an de grâce 1985, au sein de la rédaction d’un numéro spécial de la revue de Van Boghout sur Julius Evola, dossier qui sera repris partiellement par la revue évolienne française “Totalité” de Georges Gondinet. C’était au temps béni du meilleur adjoint que Van Boghout ait jamais eu: l’étonnant, l’inoubliable Frank Goovaerts, qui pratiquait les arts martiaux japonais jusque dans l’archipel nippon, traversait chaque été la France en moto, jouait au bridge comme un lord anglais et était ouvrier sur les docks d’Anvers; il fut assassiné dans la rue par un dément en 1991. Dans les colonnes de “Dietsland-Europa”, Tommissen a évoqué son cher Carl Schmitt, qui le méritait bien, le livre de Bertram sur Nietzsche, Hans Freyer (dont on ne connait que trop peu de choses dans l’espace linguistique francophone), Pareto, les courants de droite sous la République de Weimar, la théorie schmittienne des grands espaces et la notion évolienne de décadence.

L’appel de Carl Schmitt: devenir des “Gardiens des Sources”

Au cours de cette période —j’ai alors entre 18 et 24 ans— j’apprends, sans doute de la bouche d’Eemans, que la Flandre, et plus particulièrement l’Université de Louvain, avait connu pendant l’entre-deux-guerres, à l’initiative du Prof. Victor Leemans, une “Politieke Academie”, dynamique think tank focalisé sur tous les thèmes de la sociologie et de la politologie qui nous intéressaient. Tommissen s’est toujours voulu incarnation de l’héritage, réduit à sa seule personne s’il le fallait et s’il n’y avait pas d’autres volontaires, de cette “Politieke Academie”. Il a oeuvré dans ce sens, en laissant un maximum de traces écrites car, on le sait, “les paroles s’envolent, les écrits restent”. C’est la raison pour laquelle il est resté un “octogénaire hyperactif”, comme le soulignait très récemment Peter Wim Logghe, rédacteur en chef de “Teksten , Kommentaren en Studies”. Pourquoi? Parce que, dans ses “Verfassungsrechtlichen Aufsätze” et plus particulièrement dans la 5ème subdivision de la 17ème partie de ce recueil, intitulée “Savigny als Paradigma der ersten Abstandnahme von der gesetzesstaatlichen Legalität”, Carl Schmitt a réclamé, non pas expressis verbis mais indirectement, l’avènement d’une sorte de centrale intellectuelle et spirituelle, qu’il évoquait sous le nom poétique de “Hüter der Quellen”, “les Gardiens des Sources”. Voilà ce que Tommissen a voulu être: un “Gardien des Sources”, dût-il se maintenir à son poste comme le soldat de Pompéi ou d’Herculanum, en dépit des flots de lave qui s’avançaient avec fureur face à lui. Quand la lave refroidit et se durcit, on peut en faire de bons pavés de porphyre, comme celui de Quenast. Avec la boue “enchimiquifiée” et les eaux résiduaires de la société de consommation, on tuera jusqu’à la plus indécrottable des chienlits. Petite méditation spenglerienne et pessimiste...

La “Politieke Academie”

Nous aussi, nous interprétions, sans encore connaître ce texte fondamental de Schmitt, notre démarche métapolitique, au dedans ou en dehors de la “nouvelle droite”, peu importait, comme une démarche de “gardien des sources”. Alors qu’avons nous fait? Nous avons entamé une recherche de textes émanant de cette “Politieke Academie” et de ce fascinant Prof. Leemans. Nous avons trouvé son Sombart, son Marx, son Kierkegaard, que nous comparions aux textes sombartiens édités par Claudio Mutti et Giorgio Freda en Italie, aux rares livres de Sombart encore édités en Allemagne, notamment chez DTV; nous cherchions à redéfinir les textes marxiens à la lumière des dissidents de la IIème et de la IIIème Internationales (Lassalle, Dühring, De Man,...). Mais la “Politieke Academie” avait des successeurs indirects: nous plongions dans les trois volumes de monographies didactiques sur la vie et l’oeuvre des grands sociologues contemporains que la célèbre collection “Aula” offrait à la curiosité des étudiants néerlandais et flamands (“Hoofdfiguren uit de sociologie”); seul germaniste dans le groupe, j’ajoutais les magnifiques ouvrages de Helmut Schoeck (dont: “Geschichte der Soziologie – Ursprung und Aufstieg der Wissenschaft von der menschlichen Gesellschaft”). Tout cela constituait un complexe de sociologie et de sciences politiques tonifiant; avec cela, nous étions à des années-lumière des petits exercices insipides de statistiques étriquées et de meccano “organisationnel” à l’américaine, nappé de la sauce vomitive du “politiquement correct”, qu’on propose aujourd’hui aux étudiants, en empêchant du même coup l’avènement d’une nouvelle élite, prête à amorcer un nouveau cycle sociologique parétien, en coupant l’herbe sous les pieds d’avant-gardistes qui sont tout à la fois révolutionnaires et “gardiens des sources”.

A cette époque de grande effervescence intellectuelle et de maturation, nous avons rencontré le Professeur Tommissen à la tribune du “Centro Studi Evoliani” de Marc. Eemans, où il a animé une causerie sur Pareto et une autre sur Schmitt. Nous connaissions mieux Pareto grâce à l’excellent ouvrage de Julien Freund sur le sociologue et économiste italien, paru à l’époque chez Seghers. Notre rapport à Schmitt, à l’époque, était indirect: il passait invariablement par l’ouvrage de Freund: “Qu’est-ce que le politique?”. De Carl Schmitt lui-même, nous ne disposions que de “La notion du politique”, publié chez Calmann-Lévy, grâce à l’entremise de Julien Freund, sans que nous ne connaissions véritablement le contexte de l’oeuvre schmittienne. Celle-ci n’était accessible que via des travaux académiques allemands, difficilement trouvables à Bruxelles. Finalement, j’ai obtenu les références nécessaires pour aller commander les ouvrages-clefs du “solitaire de Plettenberg” chez ce cher librairie de la rue des Comédiens, au coeur de la vieille ville de Bruxelles. Résultat: une ardoise, alors considérable, de 5000 francs belges, que mon père est allé apurer, tout à la fois catastrophé et amusé. Une bêtise d’étudiant, à ses yeux... Nous étions au printemps de l’année 1980 et une partie de l’ardoise (il n’y avait pas seulement les 5000 francs résiduaires payés par mon géniteur...) avait été généreusement offerte par le Bureau de traduction de Mr. Singer, chez qui j’avais effectué mon stage pratique obligatoire de fin d’études. Singer, germanophone issu de la communauté israélite berlinoise, aimait les étudiants qui avaient choisi la langue allemande: il voulait toujours leur offrir des livres qui exprimaient la pensée nationale allemande, sinon des ouvrages qui communiquaient à leurs lecteurs l’esprit prussien de discipline. Quand je lui ai suggéré de me financer du Carl Schmitt, Singer, déjà octogénaire et toujours sur la brèche, était enchanté. Et voilà comment, de Tommissen à Singer, et de “Over en in zake Carl Schmitt” jusqu’à la pharamineuse commande au libraire de la rue des Comédiens, a commencé mon itinéraire personnel de schmittien en herbe. Inutile de préciser, que cet itinéraire est loin d’être achevé...

“Nouvelle école”: Tommissen à mon secours

En 1981, très exactement à la date du 15 mars, je débarque avec mes parents et mes bagages à Paris, où me reçoivent les amis Gibelin et Garrabos. J’étais devenu le secrétaire de rédaction de “Nouvelle école”, la très belle revue de l’inénarrable et fantasque de Benoist. Celui-ci, avec l’insouciance et l’impéritie de l’autodidacte parisien prétentieux, avait décidé de me faire fabriquer des numéros de “Nouvelle école” sur Pareto et sur Heidegger. C’est évidemment de la candeur de journaliste. Comment peut-on demander à un galopin de tout juste 25 ans, qui n’a pas étudié les sciences politiques ou la philosophie, de fabriquer de tels dossiers en un tourne-main? Tout simplement parce qu’on est un farfelu. Mais, moi, on ne m’a jamais appris à discuter, d’ailleurs Schmitt abhorrait la discussion à l’instar de Donoso Cortès. Il fallait obéir aux ordres et aux consignes: il fallait agir et produire ce qu’il fallait produire. Donc il a bien fallu que je m’exécute, sans trop gaffer. Comment? Eh bien, en m’adressant aux deux seules personnes, que je connaissais, qui avaient pratiqué Pareto à niveau universitaire: Bernard Marchand et Piet Tommissen! Bernard Marchand avait rédigé un mémoire à l’UCL sur les néo-machiavéliens, tels que James Burnham les avait présentés. Il nous a livré, à titre d’introduction, une version adaptée et complétée de son mémoire. Tommissen est ensuite venu à mon secours et m’a confié des textes de lui-même et d’un certain Torrisi. Guillaume Faye, plus branché sur les sciences politiques, a commis un excellent texte sur la notion de doxanalyse qu’il avait tiré de sa lecture très attentive des oeuvres de Jules Monnerot. D’où: première mission accomplie! Réaction grognone de de Benoist, dans l’affreux bouge dégueulasse de restaurant, qui se trouvait à côté des bureaux du GRECE, rue Charles-Lecocq dans le 15ème, et où il avait l’habitude de se “restaurer”: “C’est la colonisation belge... Je vais finir par m’appeler Van Benoist et, toi, Guillaume, tu t’appeleras Van Faye...”. Il ne manquait plus que “Van Vial” et “Van Valla” au tableau... Après cette parenthèse parisienne, où les anecdotes truculentes et burlesques ne manquent pas, il fallait que j’accomplisse mon service militaire et que je mette la dernière main à mon mémoire de fin d’études, commencé en 1980.

La défense orale de mon mémoire: encore Tommissen à mon secours!

Vu la maladie puis le départ à la retraite de mon promoteur de mémoire, Albert Defrance, je ne présente mon pensum au jury qu’en septembre 1983. Ce n’est pas un mémoire transcendant. Ecole de traduction oblige, il s’agit d’une modeste traduction, annotée, justifiée et explicitée dans son contexte. Mais elle entrait dans le cadre des sciences politiques, telles que nous les concevions. Au début, j’avais souhaité traduire un des ouvrages de Helmut Schoeck mais ceux-ci étaient tous trop volumineux pour un simple mémoire dit de “licence” (selon le vocabulaire belge, avant l’introduction du vocabulaire de Bologne). Finalement, le seul ouvrage court brossant un tableau intéressant des pistes sociologiques et politologiques que nous aimions explorer était celui d’Ernst Topitsch et de Kurt Salamun sur la notion d’idéologie. Mais problème: Defrance s’intéressait à la question mais il n’était plus là. Mon cher professeur de grammaire allemande, Robert Potelle, reprend le flambeau mais avoue, avec la trop grande modestie qui le caractérise, qu’il n’est pas habitué à manier le vocabulaire propre à ces disciplines. Frau Costa, notre professeur d’histoire allemande, fait preuve de la même modestie exagérée (“Wie haben Sie einen solchen Wortschatz meistern können?”), alors que son cours sur le passage de Weimar au national-socialisme, avec la fameuse “Ermächtigungsgesetz” fut une excellente introduction à une problématique abordée par Schmitt. Que faire? Comment trouver un universitaire germanophone spécialisé dans la thématique? C’est simple: appeler Tommissen pour qu’il soit l’un de mes lecteurs extérieurs. Rendez-vous est pris à Grimbergen, dans le foyer, antre et bibliothèque de notre professeur. Tommissen accepte: il aime la clarté et la concision de Topitsch et Salamun. Lors de la défense orale, Tommissen aiguille le débat sur une note, que j’avais ajoutée, sur la notion wébérienne de “Wertfreiheit”. Ce terme est intraduisible en français. Seul Julien Freund avait forgé une traduction acceptable: “neutralité axiologique”. En effet, si je suis “libre”, donc “frei” donc en état de “liberté”, de “Freiheit”, et si je suis dépourvu de tout “jugement impromptu de valeur”, donc si je suis “neutre”, quand j’observe une réalité sociologique ou politique, qui, elle, véhicule des valeurs, je suis en bout de course “libre de toute valeur”, donc “axiologiquement neutre”, chaque fois que je pose un regard scientifique sur un phénomène social ou politique. Weber plaçait aussi cette notion de “Wertfreiheit” dans le contexte de sa distinction entre “éthique de la responsabilité” (“Verantwortungsethik”) et “éthique de la conviction” (“Gesinnungsethik”). Ni l’une ni l’autre ne sont dépourvues de “valeur” mais la responsabilité implique un recul, un usage parcimonieux et raisonnable des ressources axiologiques tandis que la conviction peut, le cas échéant, déboucher sur des confrontations et des blocages, des paralysies ou des déchaînements, justement par absence de recul et de parcimonie comportementale.

Voilà ce que j’ai pu répondre, en bon allemand, et ainsi obtenir une distinction. Je la dois indubitablement à l’ascendant de Tommissen et à sa manière habile de poser effectivement la question principale qu’il convenait de poser face à ce mémoire, modeste traduction.

La bibliothèque de Grimbergen

L’un des premiers textes de Piet Tommissen fut un récit de son voyage, avec son épouse Agnès, chez Carl Schmitt, à Plettenberg en Westphalie. Avec grande tendresse, Tommissen a décrit ce voyage, la réception profondément amicale que lui avait prodiguée Carl Schmitt. A mon tour de raconter aussi deux ou trois impressions de ma visite à Grimbergen, pendant l’été 1983: accueil chaleureux d’Agnès et Piet Tommissen, visite de la bibliothèque. Dans la pièce de séjour, il y avait ce fauteuil du maître des lieux, tout entouré d’étagères construites sur mesure, croulant sous le poids des livres du mois, potassés pour écrire le prochain article ou essai. Tout, dans la maison, était agencé pour faciliter la lecture. La bibliothèque de Grimbergen était fabuleuse: elle mérite bien la comparaison avec les autres grandes bibliothèques privées que j’ai eu l’occasion de visiter: celle d’Alain de Benoist évidemment; celle de Mohler, vue à Munich en plein été torride de 1984; celle, luxuriante et chaotique de Pierre-André Taguieff, véritable labyrinthe où évoluait un gros chat teigneux et espiègle; celle, somptueuse, dans la villa de Miglio, vue en mai 1995 à Côme et celle de Peter Bossdorf, la plus magnifiquement agencée, vue en automne 2010. Cette évocation des grandes bibliothèques est évidemment un clin d’oeil à Tommisen: celui-ci s’enquerrait toujours des livres achetés par ses hôtes et leur demandait d’évoquer leurs bibliothèques...

Pierre-André Taguieff à Bruxelles

Plus tard, début des années 90, quand Pierre-André Taguieff préparait son ouvrage “Sur la nouvelle droite”, paru en 1994 chez Descartes & Cie, il avait sollicité un rendez-vous avec Tommissen et avec moi-même: le soir de cette journée, nous avons dîné dans un restaurant minuscule, uniquement destiné aux gourmets, en compagnie de mon camarade Frédéric Beerens et d’un majestueux ami de Tommissen, affublé d’une énorme barbe rousse qui lui couvrait un poitrail de taureau. Discussion à bâtons rompus, surtout entre Taguieff et Tommissen sur la personnalité de Julien Freund. On reproche à Taguieff certains travaux jugés inquisitoriaux sur la “nouvelle droite” ou sur les mouvements populistes (l’ouvrage de Taguieff sur “L’illusion populiste” est d’ailleurs le plus faible de ses ouvrages: les chapitres concernant la Flandre et l’Autriche ne comportent aucune référence en langue néerlandaise ou allemande!). Mais il faut rendre hommage au philosophe qui a critiqué le “bougisme” contemporain et a assorti cette critique d’un appel à la résistance de toutes les forces politiques qui n’entendent pas s’aligner sur les poncifs dominants. Ensuite, l’oeuvre majeure de Pierre-André Taguieff, “L’effacement de l’avenir” deviendra indubitablement un grand classique: on y découvre un excellent constat de faillite du “progrès”, une critique extrêmement pointue du présentisme ainsi qu’une critique fort pertinente des nouvelles formes de fausse démocratie qui ne sont, explique Taguieff, que des “expertocraties”. On peut évoquer ici le “double langage” de Taguieff, non pas au sens orwellien du terme, où la “liberté” serait l’ “esclavage”, mais dans le sens où nous avons affaire à un théoricien en vue de la gauche mitterrandienne et post-mitterrandienne, obsédé par le joujou “racisme” comme il y avait un “joujou nationalisme” du temps de Rémy de Gourmont, un intellectuel post-mitterrandien qui a pondu une triclée de travaux sur cette notion-joujou qui n’a pas d’autre existence ou de statut que ceux de “bricolages médiatiques”; au fond: s’il existe à l’évidence des préjugés raciaux, cela n’empêchera nullement le pire des racistes de trouver un jour son bon “nègre”, son “bon arbi” ou son juif favori. Même le Troisième Reich recrutait Blancs, Blacks et Beurs, et Indiens bouddhistes, hindouistes, musulmans ou sikhs, pourvu qu’il s’agissait de lutter contre la ploutocratie britannique. Et le plus acharné des anti-racistes fulminera un jour contre un représentant quelconque d’une autre race que la sienne ou sera agité par un prurit antisémite; dans la vie quotidienne les exemples sont légion. Quant aux Blancs, ils sont tout aussi victimes de préjugés raciaux que les autres.

Taguieff situe ses propres travaux sur le racisme et l’anti-racisme dans le cadre d’un axe de recherches inauguré par l’Américain Gordon W. Allport (“The Nature of Prejudice”, 1ère éd., 1954): le danger que recèle ce genre de démarche, qui est propre à un certain libéralisme totalitaire, est d’amorcer une critique des “préjugés” qui amènera à un rejet puis à un arasement des “valeurs”, posées derechef comme des “irrationalités” à gommer, des valeurs sans lesquelles aucune société ne peut toutefois fonctionner, sans lesquelles toute société devient, pour reprendre la terminologie du Prof. Marcel De Corte, principal collaborateur d’Eemans au temps de la revue “Hermès” (1933-1939), une “dissociété”. Taguieff est conscient de ce danger car son idéologie “républicaine” (certes plus nuancée que les insupportables vulgates que l’on entend ânonner à longueur de journées) n’est pas dépourvue de “valeurs”, notamment de “valeurs citoyennes”, qui risquent l’arasement au même titre que les valeurs catholiques, conservatrices ou “raciques” (dans la mesure où elles sont vernaculaires), pour le plus grand bénéfice de l’idéologie présentiste qui conçoit la société non pas comme une communauté de destin mais comme un supermarché. Taguieff est donc ce penseur post-mitterrandien, qui a partagé l’illusion de la grande foire multiraciale annoncée par les “saturnales de touche-pas-à-mon-pote” (dixit Louis Pauwels), et, simultanément, le penseur d’une “nouvelle révolution conservatrice” à la française, une “révolution conservatrice” qui critique de fond en comble la notion fétiche de progrès. C’est en ce sens que j’ai voulu présenter ses ouvrages lors d’une université d’été de “Synergies Européennes” en Basse-Saxe. Taguieff mérite maintenant plus que jamais ce titre de “théoricien révolutionnaire-conservateur” car il a oeuvré d’arrache-pied pour poursuivre, défendre et illustrer l’oeuvre de Julien Freund. Quant à la critique des préjugés, mieux vaut se plonger dans les écrits et les pamphlets de ceux qui luttent contre le festivisme (Philippe Muray), facteur d’un impolitisme total, ou contre les vrais préjugés et débilités du “politiquement correct” comme Elizabeth Lévy, Emmanuelle Duverger ou Robert Ménard. Ce sont là critiques bien plus tonifiantes.

Après le dîner avec Tommissen et son ami barbu, Beerens et moi avons ramené notre bon Taguieff à son hôtel: n’ayant pas le coffre et l’estomac breugheliens comme les nôtres, il est revenu de nos agapes en état de franche ébriété; sur la banquette arrière de la petite Volkswagen de Beerens, il émettait de joyeuses remarques: “je suis un être dédoublé, ha ha ha, un bon joueur d’échecs, hi hi hi, je parle avec tout le monde, hu hu hu, et je roule tout le monde, ha ha ha!”. Enfin un intellectuel parisien qui se comportait comme nos joyeux professeurs qui manient allègrement la chope de bière, comme Tommissen ou l’angliciste Heiderscheidt, ou comme l’heideggerien Gadamer, qui participait, presque centenaire, aux canti de ses étudiants et tenait à respecter les règles des festivités estudiantines. Dommage que Taguieff ne soit pas resté longtemps ou ne soit jamais revenu: on en aurait fait un bon disciple de Bacchus et du Roi Gambrinus! En réalité, c’est vrai, il est un “être dédoublé”, in vino veritas, mais il ne “roule” pas tout le monde, il séduit tout le monde, tant les tenants de la gôôôche de toujours que les innovateurs qui puisent dans le vrai corpus de la “révolution conservatrice”!

La Foire du Livre à Francfort

Mais où Tommissen était le plus présent, sans y être physiquement, c’était à la Foire du Livre de Francfort, que j’ai visitée de 1984 à 1999, ainsi qu’en 2003. Pour moi, la Foire du Livre de la métropole hessoise a toujours été “maschkinocentrée”, c’est-à-dire centrée autour de la truculente personnalité de Günter Maschke, cet ancien révolutionnaire de mai 68, devenu schmittien, un des plus grands schmittiens de la Planète Terre au fil du temps. Et qui dit Günter Maschke, dit Carl Schmitt et tout l’univers des schmittiens. Après avoir arpenté pendant toute la journée les énormes halls de la Foire, nous nous retrouvions fourbus le soir chez Maschke, pour discuter de tout, mais pas dans une ambiance compassée, faite de sérieux papal: nous avons sorti les pires énormités, en riant comme des collégiens ou des soudards qui venaient d’achever une bataille. A la table, outre le grand expert militaire suisse Jean-Jacques Langendorf, et le Dr. Peter Weiss, directeur de la maison d’édition “Karolinger Verlag”, nous avions très souvent le bonheur d’accueillir le grand philosophe grec Panayotis Kondylis et l’écrivain allemand Martin Mosebach. Dans ces joyeuses retrouvailles annuelles, Maschke évoquait toujours Tommissen avec le plus grand respect. En effet, de 1988 à 2003, Piet Tommissen a publié ses miniatures sur Carl Schmitt dans la série “Schmittiana”, chez le prestigieux éditeur berlinois Duncker & Humblot, acquerrant la célébrité dans l’univers restreint des bons politologues, qui sont tous, évidemment, des schmittiens, où qu’ils vivent sur le globe! Le système Tommissen, celui de la note pertinente, y a fait merveille: en quoi consiste l’excellence de ce système? Eh bien, il aiguille le train de la recherche vers des voies souvent insoupçonnées. Schmitt a rencontré telle personnalité, lu tel livre, participé à tel colloque: Tommissen explicitait en peu de mots l’intérêt de cette rencontre, de cette lecture ou de cette participation pour le reste ou la suite de l’oeuvre et ouvrait simultanément des perspectives nouvelles et inédites sur la personnalité rencontrée, l’auteur du livre lu par Schmitt ou les organisateurs du colloque qui avait bénéficié de sa participation. La même méthode vaut bien entendu pour Eemans et le champs énorme que celui-ci a couvert en tant que peintre avant-gardiste, éditeur de revues originales, historien de l’art. On a pu se moquer de cette méthode: à première vue et pour un esprit borné, elle peut paraître désuète mais, à l’analyse, elle porte des fruits insoupçonnés. Enfin, en 1997, nous avons pu célébrer la parution de “In Sachen Carl Schmitt” auprès de “Karolinger Verlag”, avec une analyse des textes satiriques de Carl Schmitt et une autre sur la correspondance Schmitt/Michels.

Alberto Buela et Horacio Cagni à Bruxelles

J’ai eu aussi le bonheur de recevoir un jour à Bruxelles le Dr. Alberto Buela et le Dr. Horacio Cagni du CNRS argentin. Ils voulaient voir trois personnes: Tommissen, dont ils n’avaient pas l’adresse, Christopher Gérard, l’éditeur de la revue “Antaios”, et moi-même. Ce ne furent que joie et libations. D’abord en l’estaminet aujourd’hui disparu que fut “Le Père Faro” à Uccle, ensuite sur la terrasse de “chez Karim”, Place de l’Altitude Cent, où la faconde de Buela, philosophe, professeur d’université, sénateur et rancher argentin, fascinait les autres clients et même les passants qui s’arrêtaient et commandaient un verre de vin, pour avoir l’insigne plaisir de l’entendre discourir! Bref, comme me disait en juin dernier un animateur de la radio “Méridien Zéro” (Paris): la métapolitique par la joie ! “Metapolitik durch Freude”! Le lendemain: à quatre, Buela, Cagni, Gérard et moi, nous prenions le train vers Vilvorde, où nous attendait Tommissen pour nous véhiculer jusqu’à Grimbergen. Nouvelle visite de la bibliothèque où le maître des lieux me montre une collection complète de mes “Orientations”, magnifiquement reliée et placée dans la bibliothèque aux côtés d’autres revues du même acabit. Et toujours le fauteuil, entouré d’étagères sur mesure... Ensuite, libations dans une salle jouxtant l’Abbaye et la Collégiale Saint Servais de Grimbergen: les bières de l’Abbaye, généreusement offertes par Tommissen, ont coulé dans nos gosiers. Thème du fructueux débat entre Tommissen et Buela: Carl Schmitt et l’Amérique latine. On sait que Buela écrit inlassablement des articles philosophiques à dimensions véritablement politiques (au sens de Schmitt et de Freund), et qui gardent une mesure grecque, au départ d’auteurs hispaniques, marqués par la tradition espagnole et par l’antilibéralisme de Donoso Cortès, qui ont tant fasciné Carl Schmitt.

Visite à Uccle

Après la mort prématurée de son épouse Agnès, Tommissen, au fond, était inconsolable. La grande maison de Grimbergen était devenue bien vide, sans la bonne fée du foyer. Notre professeur a pris alors la décision de s’établir à Uccle, dans un complexe résidentiel pour seniors, où il s’est acheté un studio, dans lequel il a empilé la quintessence de sa bibliothèque. Là il rédigera ses “Buitenissigheden”, ses “Extravagances”, et sans doute les dernières livraisons de ses “Schmittiana”. Je lui ai rendu visite deux fois, d’abord avec ma future épouse Ana, ensuite avec mon fils. Lors de notre première visite, il m’a offert ses “Nieuwe Buitenissigheden”, avec de la matière à traiter fort bientôt car, en effet, ce petit volume aux apparences fort modestes, contient trois thématiques qui m’intéressent: Wies Moens comme avant-gardiste et “révolutionnaire conservateur” flamand et nationaliste. Un auteur qui fascinait également Eemans et a sans doute contribué à déterminer ses choix, quand il entra en dissidence définitive et orageuse par rapport au groupe surréaliste bruxellois, autour de Magritte, Mariën, Scutenaire et les autres. Il me reste à travailler cette matière “Moens” et à l’exposer un jour au public francophone. Deuxième thématique: la “Politieke Academie”, dont il s’agira de réactiver les projets jusqu’à la consommation des siècles. Troisième thématique: la théorie de Brück, qui fascinait les rois Albert I et Léopold III, et qui sous-tend une variante du “suprématisme” anglo-saxon. Mais, infatigable, et porté par la ferme volonté d’écrire jusqu’à son dernier souffle, pour témoigner, révéler, arracher à l’oubli ce que ne méritait pas de l’être, Tommissen avait également sorti en 2005, “Driemaal Spengler”, un recueil de trois maîtres articles sur Oswald Spengler, parmi lesquels une étude sur la réception de l’auteur du “Déclin de l’Occident” en Flandre. La réception, lors de cette première visite à l’appartement d’Uccle, fut joviale. Notre professeur était au mieux de sa forme.

Juillet 2011: ultime visite

Notre dernière visite, début juillet 2011, cinq semaines avant sa disparition et sous une chaleur caniculaire, avait pour objet premier de lui communiquer, entre autres documents, une copie d’un entretien que l’on m’avait demandé sur Marc. Eemans et le “Centro Studi Evoliani”. Cet entretien se référait souvent à la monographie que Tommissen avait consacrée au “surréaliste pas comme les autres”. Cet entretien a plu à beaucoup de monde, y compris au nationaliste révolutionnaire évolien Christian Bouchet et à l’inclassable post-communiste Alain Soral qui l’ont immédiatement affiché sur leurs sites respectifs. Pour définir les positions d’Eemans dans cet univers avant-gardiste et surréaliste, je ne pouvais pas trouver de meilleur inspirateur que Tommissen. J’ai trouvé notre Professeur assez fatigué mais il faut dire aussi que l’après-midi de notre visite était particulièrement chaud, lourd et malsain. La conversation s’est déroulée en trois volets: Eemans et les cercles politico-littéraires ou politico-philosophiques des années 30 en Belgique, avec surtout la présence à Pontigny de Raymond De Becker qui y évoqua le néo-socialisme de De Man et Déat, un thème récurrent dans les recherches de Tommissen; le cercle “Communauté” fondé par Henry Bauchau et De Becker; leur “académie” à laquelle participait Marcel De Corte, également collaborateur de la revue “Hermès” d’Eemans; l’évolution de Bauchau et De Becker vers la psychanalyse jungienne (et les retombées de cet engouement sur Hergé) et la participation de De Becker à la revue “Planète” de Louis Pauwels. Sans compter l’impasse dans laquelle s’est retrouvée l’intelligentsia “conservatrice” ou “révolutionnaire-conservatrice” ou “non-conformiste des années 30” en Belgique, à partir du moment où l’Action Française de Maurras est condamnée par le Vatican en 1926; pour remplacer l’idole Maurras, désormais à l’index, une partie de cette intelligentsia va changer de gourou et adopter Jacques Maritain. Les vicissitudes de cette transition, que n’a pas vécu l’intelligentsia flamande, expliquent sans doute le peu de rapports entre les intellectuels des deux communautés linguistiques, ou le caractère très ténu de leurs références communes. Enfin, l’étude de Tommissen sur le rapport entre Francis Parker Yockey et la chorégraphe flamande Elsa Darciel (cf. euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/ ). Au cours de l ‘entretien, mon fiston et moi-même fûmes gâtés: deux volumes autobiographiques de Tommissen (“Een leven vol buitenissigheden”) et un volume avec la bibliographie complète des oeuvres de notre professeur. Deuxième volet: Tommissen n’a cessé d’interroger mon fils sur les innovations à la KUL, sur l’état d’esprit qui y règne, sur les matières qui y sont enseignées, etc. Troisième volet, avec mon épouse; Tommissen n’importunait jamais les dames avec ses engouements politiques ou philosophiques, il passait aux thèmes de la vie quotidienne et de la famille. Il nous a dit: “Aimez-vous et profitez des bons côtés de la vie”. Ce fut notre dernière rencontre.

Nous avions promis de nous revoir en septembre pour poursuivre nos conversations: cette année les voies du dépaysement estival nous ont menés tour à tour en Zélande, dans l’Eifel et les Fagnes, au Cap Blanc-Nez et sur la côte d’Opale, dans la Baie de la Somme, à Oslo, dans les Vosges et en Franche-Comté, sur le Chasseral suisse et sur les bords du Lac de Neuchâtel. Le 21 août, deux jours après notre retour de cette escapade dans le Jura, Piet Tommissen s’éteignait à Uccle. Une magnifique et émouvante cérémonie a eu lieu à Grimbergen le 26 août, ponctuée par le “Gebed aan ’t Vaderland”.

Avec la disparition de Piet Tommissen, ce sont des pans entiers de souvenirs, de la mémoire intellectuelle de la Flandre, qui disparaissent. Mais, avec lui, une chose est sûre: nous savons ce que nous devons faire jusqu’à notre dernier souffle de vie. Nous devons témoigner, lire, recenser, repérer des anecdotes en apparence futiles mais qui expliquent les transitions, notamment les transitions qui partent de la gauche officielle pour aboutir à des gauches non conformistes comme celles que parcoururent Pierre Hubermont ou Walter Dauge en Wallonie, celles qu’empruntèrent Eemans ou Moens qui, tous deux, mêlent étroitement avant-gardes, militantisme flamand et engouements philosophiques traditionnels. Nous devons aussi rester des schmittiens, attentifs à tous les aspects de l’oeuvre du “catholique prussien du Sauerland”. Car il s’agit de demeurer, envers et contre toutes les déchéances, tous les impolitismes et tous les festivismes, des “Gardiens des sources”.

En attendant, nous devons encore dire “Merci! Mille mercis!” à Piet Tommissen, pour sa gentillesse et pour son érudition.

Robert STEUCKERS.

Rédigé, grande tristesse au coeur, à Forest-Flotzenberg, le 4 septembre 2011.

Si è spento lo scorso 21 agosto Piet Tommissen, sociologo ed economista belga, noto per i suoi studi su Vilfredo Pareto e Carl Schmitt, del quale fu amico e bibliografo e alla cui opera, a lungo negletta, ha dedicato una quantità di scritti che hanno contribuito a diffonderla su scala internazionale. Molto stretto fu anche il suo rapporto con Julien Freund. Tommissen – “il matto” come lo definiva amabilmente Gianfranco Miglio – è stato senz’altro uno degli esponenti più in vista della tradizione del realismo politico europeo e un punto di riferimento per tutti i giovani studiosi che a questa tradizione si sono richiamati nel corso degli anni. Lo ricordiamo pubblicando l’omaggio che in occasione dei suoi 75 anni, nel 2000, gli ha dedicato Günter Maschke, a sua volta amico ed editore di Schmitt, nonché curatore di alcune sue importanti raccolte di scritti.

Si è spento lo scorso 21 agosto Piet Tommissen, sociologo ed economista belga, noto per i suoi studi su Vilfredo Pareto e Carl Schmitt, del quale fu amico e bibliografo e alla cui opera, a lungo negletta, ha dedicato una quantità di scritti che hanno contribuito a diffonderla su scala internazionale. Molto stretto fu anche il suo rapporto con Julien Freund. Tommissen – “il matto” come lo definiva amabilmente Gianfranco Miglio – è stato senz’altro uno degli esponenti più in vista della tradizione del realismo politico europeo e un punto di riferimento per tutti i giovani studiosi che a questa tradizione si sono richiamati nel corso degli anni. Lo ricordiamo pubblicando l’omaggio che in occasione dei suoi 75 anni, nel 2000, gli ha dedicato Günter Maschke, a sua volta amico ed editore di Schmitt, nonché curatore di alcune sue importanti raccolte di scritti.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

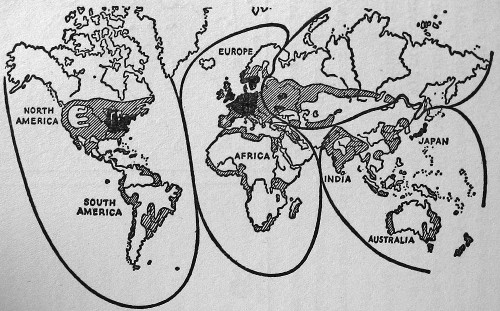

Haushofer’s radically continentalist and anti-thalassocratic thought came into focus in 1941, when he published Der Kontinentalblock-Mitteleuropa-Eurasien-Japan (The Continental Bloc Central Europe-Eurasia-Japan). Written after the Germano-Soviet pact, this work argued for a Germano-Italo-Soviet-Japanese alliance that would radically reorganize the Eurasian continental mass. He stressed that the permanent fear of the Anglo-Saxons is the emergence of a Berlin-Moscow-Tokyo axis, which would completely escape the influence of the commercial thalassocracies, which, he writes, practice the policy of the anaconda, which consists in gradually encircling and slowly suffocating its prey. But a unified Eurasia would be too large for the Anglo-American anaconda. Thanks to its gigantic mass, it could resist any blockade.

Haushofer’s radically continentalist and anti-thalassocratic thought came into focus in 1941, when he published Der Kontinentalblock-Mitteleuropa-Eurasien-Japan (The Continental Bloc Central Europe-Eurasia-Japan). Written after the Germano-Soviet pact, this work argued for a Germano-Italo-Soviet-Japanese alliance that would radically reorganize the Eurasian continental mass. He stressed that the permanent fear of the Anglo-Saxons is the emergence of a Berlin-Moscow-Tokyo axis, which would completely escape the influence of the commercial thalassocracies, which, he writes, practice the policy of the anaconda, which consists in gradually encircling and slowly suffocating its prey. But a unified Eurasia would be too large for the Anglo-American anaconda. Thanks to its gigantic mass, it could resist any blockade. The idea of a tripartite alliance first occurred to the Japanese and Russians. At the time of the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, when the British and Japanese united against the Russians, some of the Japanese leadership—including Hayashi, their ambassador in London, Count Gato, Prince Ito, and Prime Minister Katsura—desired a Germano-Russo-Japanese pact against the English seizure of global sea traffic. The visionary Count Gato recommended a troika in which the central horse, the strongest one, flanked by two lighter and more nervous horses, Germany and Japan. In Russia, the Eurasian idea would be incarnated a few years later by the minister Sergei Witte, the creative genius of the Trans-Siberian Railroad who in 1915 advocated a separate peace with the Kaiser.

The idea of a tripartite alliance first occurred to the Japanese and Russians. At the time of the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, when the British and Japanese united against the Russians, some of the Japanese leadership—including Hayashi, their ambassador in London, Count Gato, Prince Ito, and Prime Minister Katsura—desired a Germano-Russo-Japanese pact against the English seizure of global sea traffic. The visionary Count Gato recommended a troika in which the central horse, the strongest one, flanked by two lighter and more nervous horses, Germany and Japan. In Russia, the Eurasian idea would be incarnated a few years later by the minister Sergei Witte, the creative genius of the Trans-Siberian Railroad who in 1915 advocated a separate peace with the Kaiser.

Il y a cent ans, Péguy publiait Le mystère de la Charité de Jeanne d’Arc, pièce de théâtre qui est toute entière le mystère de la prière de Péguy. Il publiait aussi, cette même année 1911, Le Porche du mystère de la deuxième Vertu (« Ce qui m’étonne, dit Dieu, c’est l’espérance. » Cette « petite fille espérance. Immortelle » que chantera cet autre poète qu’était Brasillach). L’occasion de revenir sur Péguy, l’homme de toutes les passions.

Il y a cent ans, Péguy publiait Le mystère de la Charité de Jeanne d’Arc, pièce de théâtre qui est toute entière le mystère de la prière de Péguy. Il publiait aussi, cette même année 1911, Le Porche du mystère de la deuxième Vertu (« Ce qui m’étonne, dit Dieu, c’est l’espérance. » Cette « petite fille espérance. Immortelle » que chantera cet autre poète qu’était Brasillach). L’occasion de revenir sur Péguy, l’homme de toutes les passions. Hoe revoluties ontstaan, is een vraag die men zich al heel lang stelt. De actualiteit van de zogenaamde Arabische Lente in 2011 heeft ondertussen geleerd dat er geen antwoorden bestaan, die het fenomeen op zich volledig verklaren. Maar het Franse tijdschrift, La Nouvelle Revue d’Histoire, fraai uitgegevendoor Dominique Venner en één van de beste van zijn soort, heeft het nodig gevonden om hieraan een dossier te wijden. Een dossier dat net op tijd komt, want net rond deze periode werd ook het hoofdwerk van José Ortega y Gasset , La Rebelion De Las Masas (vertaal in het Nederlands als De Opstand der Horden, verschenen bij Nijgh & Van Ditmar met ISBN-nummer 9789023655671) opnieuw in het Frans uitgegeven.

Hoe revoluties ontstaan, is een vraag die men zich al heel lang stelt. De actualiteit van de zogenaamde Arabische Lente in 2011 heeft ondertussen geleerd dat er geen antwoorden bestaan, die het fenomeen op zich volledig verklaren. Maar het Franse tijdschrift, La Nouvelle Revue d’Histoire, fraai uitgegevendoor Dominique Venner en één van de beste van zijn soort, heeft het nodig gevonden om hieraan een dossier te wijden. Een dossier dat net op tijd komt, want net rond deze periode werd ook het hoofdwerk van José Ortega y Gasset , La Rebelion De Las Masas (vertaal in het Nederlands als De Opstand der Horden, verschenen bij Nijgh & Van Ditmar met ISBN-nummer 9789023655671) opnieuw in het Frans uitgegeven. onderwijs zichenorm en zorgden democratische rechten ervoor dat een ongekende situatie ontstond. Voor de eerste keer in de geschiedenis “oefenden individuen, die onverschillig stonden tegenover verleden en toekomst, die geen bijzondere ambitie of passie hadden, het recht uit om het lot van de wereld in een bepaalde richting te sturen” (Jean Michel Baldassari, pag. 35).

onderwijs zichenorm en zorgden democratische rechten ervoor dat een ongekende situatie ontstond. Voor de eerste keer in de geschiedenis “oefenden individuen, die onverschillig stonden tegenover verleden en toekomst, die geen bijzondere ambitie of passie hadden, het recht uit om het lot van de wereld in een bepaalde richting te sturen” (Jean Michel Baldassari, pag. 35). Hannah Arendt, die in haar De oorsprong van het totalitarisme het spiritueel ontworteld individu beschrijft datzeer gevoelig is voor collectivistische avonturen, zo vreest ook Ortega y Gasset de irrationele kracht van massa. Hij stond dus eerder afkerig van het Italië van Mussolini, maar was bovenal een anticommunist.

Hannah Arendt, die in haar De oorsprong van het totalitarisme het spiritueel ontworteld individu beschrijft datzeer gevoelig is voor collectivistische avonturen, zo vreest ook Ortega y Gasset de irrationele kracht van massa. Hij stond dus eerder afkerig van het Italië van Mussolini, maar was bovenal een anticommunist.

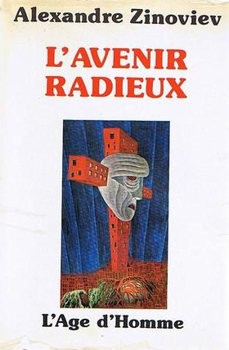

Students and observers of communism consistently encounter the same paradox: On the one hand they attempt to predict the future of communism, yet on the other they must regularly face up to a system that appears unusually static. At Academic gatherings and seminars, and in scholarly treatises, one often hears and reads that communist systems are marred by economic troubles, power sclerosis, ethnic upheavals, and that it is only a matter of time before communism disintegrates. Numerous authors and observers assert that communist systems are maintained in power by the highly secretive nomenklatura, which consists of party potentates who are intensely disliked by the entire civil society. In addition, a growing number of authors argue that with the so-called economic linkages to Western economies, communist systems will eventually sway into the orbit of liberal democracies, or change their legal structure to the point where ideological differences between liberalism and communism will become almost negligible.

Students and observers of communism consistently encounter the same paradox: On the one hand they attempt to predict the future of communism, yet on the other they must regularly face up to a system that appears unusually static. At Academic gatherings and seminars, and in scholarly treatises, one often hears and reads that communist systems are marred by economic troubles, power sclerosis, ethnic upheavals, and that it is only a matter of time before communism disintegrates. Numerous authors and observers assert that communist systems are maintained in power by the highly secretive nomenklatura, which consists of party potentates who are intensely disliked by the entire civil society. In addition, a growing number of authors argue that with the so-called economic linkages to Western economies, communist systems will eventually sway into the orbit of liberal democracies, or change their legal structure to the point where ideological differences between liberalism and communism will become almost negligible.  Zinoviev refutes the widespread belief that communist power is vested only among party officials, or the so-called nomenklatura. As dismal as the reality of communism is, the system must be understood as a way of life shared by millions of government official, workers, and countless ordinary people scattered in their basic working units, whose chief function is to operate as protective pillars of the society. Crucial to the stability of the communist system is the blending of the party and the people into one whole, and as Zinoviev observes, “the Soviet saying the party and the people are one and the same, is not just a propagandistic password.” The Communist Party is only the repository of an ideology whose purpose is not only to further the objectives of the party members, but primarily to serve as the operating philosophical principle governing social conduct. Zinoviev remarks that Catholicism in the earlier centuries not only served the Pope and clergy; it also provided a pattern of social behavior countless individuals irrespective of their personal feelings toward Christian dogma. Contrary to the assumption of liberal theorists, in communist societies the cleavage between the people and the party is almost nonexistent since rank-and-file party members are recruited from all walks of life and not just from one specific social stratum. To speculate therefore about a hypothetical line that divides the rulers from the ruled, writes Zinoviev in his usual paradoxical tone, is like comparing how “a disemboweled and carved out animal, destined for gastronomic purposes, differs from its original biological whole.”

Zinoviev refutes the widespread belief that communist power is vested only among party officials, or the so-called nomenklatura. As dismal as the reality of communism is, the system must be understood as a way of life shared by millions of government official, workers, and countless ordinary people scattered in their basic working units, whose chief function is to operate as protective pillars of the society. Crucial to the stability of the communist system is the blending of the party and the people into one whole, and as Zinoviev observes, “the Soviet saying the party and the people are one and the same, is not just a propagandistic password.” The Communist Party is only the repository of an ideology whose purpose is not only to further the objectives of the party members, but primarily to serve as the operating philosophical principle governing social conduct. Zinoviev remarks that Catholicism in the earlier centuries not only served the Pope and clergy; it also provided a pattern of social behavior countless individuals irrespective of their personal feelings toward Christian dogma. Contrary to the assumption of liberal theorists, in communist societies the cleavage between the people and the party is almost nonexistent since rank-and-file party members are recruited from all walks of life and not just from one specific social stratum. To speculate therefore about a hypothetical line that divides the rulers from the ruled, writes Zinoviev in his usual paradoxical tone, is like comparing how “a disemboweled and carved out animal, destined for gastronomic purposes, differs from its original biological whole.”

Since 1945 Western nations have witnessed a dramatic reduction in the variety of positions in political theory and jurisprudence. Political argument has been virtually reduced to contests within liberal-democratic theory. Even radicals now take representative democracy as their unquestioned point of departure. There are, of course, some benefits following from this restriction of political debate. Fascist, Nazi and Stalinist political ideologies are now beyond the pale. But the hegemony of liberal-democratic political agreement tends to obscure the fact that we are thinking in terms which were already obsolete at the end of the nineteenth century.

Since 1945 Western nations have witnessed a dramatic reduction in the variety of positions in political theory and jurisprudence. Political argument has been virtually reduced to contests within liberal-democratic theory. Even radicals now take representative democracy as their unquestioned point of departure. There are, of course, some benefits following from this restriction of political debate. Fascist, Nazi and Stalinist political ideologies are now beyond the pale. But the hegemony of liberal-democratic political agreement tends to obscure the fact that we are thinking in terms which were already obsolete at the end of the nineteenth century.